The Kokoda Campaign

The Kokoda Battle

The Calm Before the Storm

In early July 1942, the jungles of Papua New Guinea were quiet. Too quiet.

Young Australian soldiers—most barely out of school, many still green to combat—were deployed into the unforgiving Owen Stanley Ranges. Their mission: protect American engineers building an airstrip at Deniki.

They were led by Lieutenant-Colonel William Owen, a former company commander from the 2/22nd Battalion, recently returned from Rabaul.

At 50, he was experienced—but he had just inherited one of the most poorly equipped and least combat-ready units in the Australian Army: the 39th Militia Battalion.

They were known as Maroubra Force. Their average age was just 18 and a half.

Still, they marched.

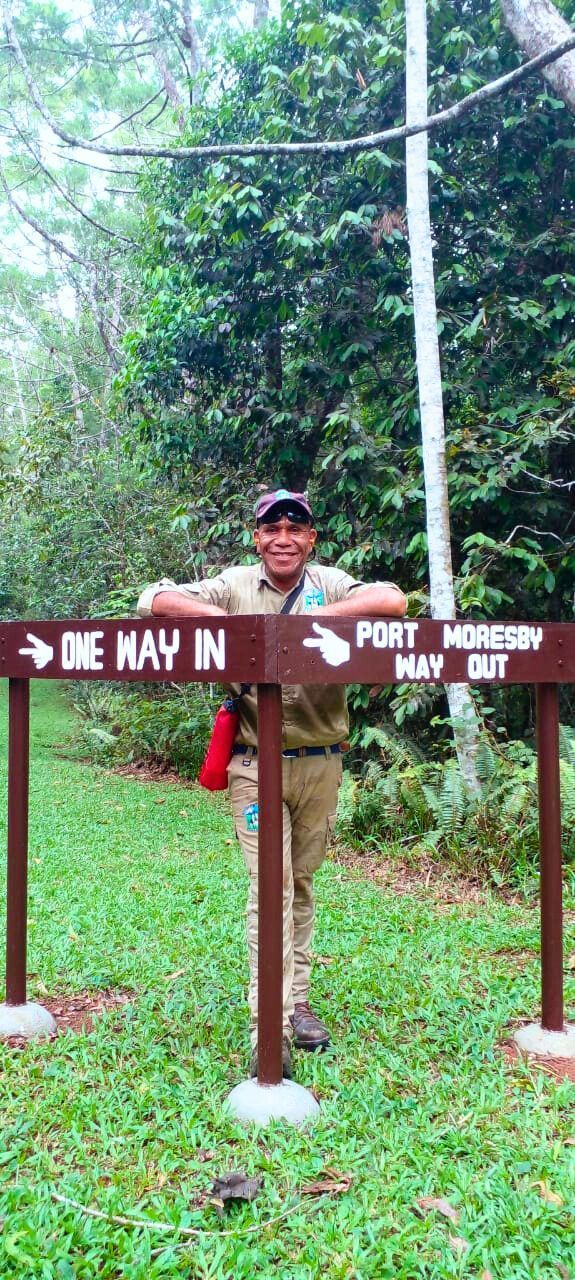

B Company, under the legendary Uncle Sam Templeton, began the trek from Owers’ Corner toward Kokoda. The track was brutal, yet this first crossing was the easiest it would ever be. Thanks to the tireless work of Bert Kienzle, a civilian with deep knowledge of the region, over 250 Papuan porters helped move their supplies across the mountainous terrain.

At

Kagi, the Australians met another 190 carriers from Kokoda. The skies were clear. The track was dry. And no one suspected that war was already on its way.

The Kokoda Track Campaign: Gona to Kokoda (August 1942)

Campaign Beginnings | First Contact | The Battle for Kokoda

Kokoda: A Jungle Outpost

By 14 July, B Company arrived in Kokoda, where they rested and trained for what lay ahead.

Meanwhile, far to the north, Colonel Yosuke Yokoyama of the Japanese Army had set sail from Rabaul with 2,000 troops. His orders were clear: land near Basabua—just east of Gona—and begin an advance toward the Owen Stanley Range.

Five days later, on 21 July, Yokoyama’s advance force landed near Gona. It included 1,400 combat troops and nearly 3,000 support personnel. They brought bicycles, construction tools, and the early momentum of an invasion force.

The Japanese were testing the possibility of a full-scale push across the Owen Stanleys toward Port Moresby.

First Contact: Soroputa and Awala

On 23 July, the first clash occurred. A small unit of Papuan Infantry Battalion (PIB) troops—just 35 men and 5 Aussie officers—made contact with Japanese forces at Soroputa, halfway between Buna and Kokoda. Led by Major William Watson, they resisted briefly before retreating across the Kumusi River, destroying a rope bridge in their wake.

Shortly after, the first Australian troops made direct contact. 11 Platoon, B Company, 39th Battalion engaged the Japanese at Awala. The contrast between the forces was stark. The Japanese were hardened veterans, drilled in jungle warfare. They wore camouflage, carried light packs, and fought with terrifying cohesion.

Not the enemy the young Australians had expected.

Second Contact: Gorari and the Battle Begins

Later that same day, 12 Platoon of B Company clashed with the Japanese at Gorari. Outnumbered and under-equipped, they executed shoot-and-scoot tactics. Five Australians were killed in the skirmish. For the 39th, it was a brutal initiation.

But something else happened too.

The survivors walked away “blooded”—their fear tempered, their resolve hardened. Templeton called it “a new swagger.”

On 24 July, B Company ambushed Japanese troops at Gorari once more. Reinforcements were sent in—D Company, armed with fresh Bren guns flown into Kokoda. Some units reached the village of Oivi, others were cut off.

At this point, the 39th Battalion was in deep. Surrounded. Alone.

The Battle at Oivi

On 26 July, the Japanese launched a full attack on the Oivi plateau. The battle lasted two hours.

At 5:00pm, Sam Templeton attempted to head back to Kokoda to warn of the scale of the enemy force—but he never arrived. He vanished into the jungle, missing in action, likely killed in the chaos.

That night, in pitch blackness, a Papuan policeman named Lance Corporal Sanopa led a surrounded Aussie platoon through the Japanese lines under cover of darkness. They made it back to Deniki. The rest, isolated at Oivi, held on through the night.

By the time Owen was fully briefed, the situation was dire.

Retaking Kokoda

On 27 July, at Deniki, Owen resolved to retake Kokoda. The next day, with 130 exhausted troops who had been fighting and patrolling for nearly three weeks, he marched back.

At 11:00am on 28 July, Owen and his men re-entered Kokoda and began digging in. They had no heavy weapons. No real reinforcements. Just shovels, rifles, and courage.

That evening, Zero fighters strafed the airfield. Japanese forces were closing in.

At 2:00am on 29 July, 210 Japanese troops launched a direct assault on the Kokoda plateau under moonlight. The Australians held their ground. Grenades flew. Rifles cracked. The jungle shook.

But then came tragedy.

At 3:00am, Lieutenant-Colonel Owen was killed—shot through the head while leading his men in classic WWI fashion. He died near the Rain Tree, under pale moonlight, defending ground that mattered.

The Australians had lost their commander.

By 4:00am, Major Watson ordered a withdrawal. Kokoda was lost.

Deniki and Aftermath

On 30 July, reinforcements from the 39th Militia arrived at Deniki. But it was too late to save Kokoda. The Japanese were already digging in.

Over the next few days, the Australians would regroup. But they had lost two commanding officers—Templeton and Owen—in as many weeks. Their lines were thin. Their nerves frayed.

Yet they did not break.

On 3 August, Bert Kienzle discovered new drop zones to the east. Supplies would soon begin to arrive by air. And on 3 November, General George Vasey would return to Kokoda to raise the flag—his presence a symbol of endurance.

Reflection: Gona to Kokoda

From 7 to 29 July 1942, the Kokoda Campaign moved from tension to fire.

The enemy had landed. The first shots had been fired. The first casualties mourned.

But something else had been forged—in the sweat, in the jungle, in the loss. A fighting spirit. A belief that even the greenest, youngest, most underprepared soldiers could hold the line.

This was the beginning. The ground between Gona and Kokoda now bore the weight of sacrifice. And the campaign had only just begun.

The Kokoda Track Campaign: Kokoda to Deniki (August 1942)

2nd Battle of Kokoda | Cameron’s Counterattack | Retreat to Deniki

Changing Command in the Fog of War

In the early days of August 1942, the fight for the Kokoda Plateau was about to reignite. The Australians had been pushed out of Kokoda. Their line had buckled—but it hadn’t broken.

Enter Major Allan Cameron, newly appointed commander of the 39th Battalion. On his journey to the front, Cameron encountered retreating members of B Company—exhausted, shaken, and heading south. Unaware of the chaos they had survived at Oivi and Kokoda, Cameron misjudged them as cowards. He branded the company disgraced, never pausing to consider that these were mostly teenage boys, some just sixteen, who had fought veteran Japanese troops with little more than bravery and borrowed rifles.

Rebuilding the Line at Deniki

By 4 August, Cameron arrived at Deniki, the forward base clinging to the ridgeline south of Kokoda. Telegraph cables had just been completed, allowing for communication with Port Moresby. Reinforcements—Company D of the 39th—marched in on 6 August, bringing total strength to around 470 men.

Their weapons were fresh from the crate—Thompson sub-machine guns, many of which they had never even seen before. They practiced with them en route. It was hardly textbook preparation.

Cameron believed Japanese strength at Kokoda was around 400. He was wrong.

A Misguided Offensive

Despite orders to hold the line and prevent the Japanese from pushing over the Owen Stanley Range, Cameron made a fateful decision: retake Kokoda.

On 8 August, he ordered a three-pronged assault.

- E Company was held in reserve at Isurava.

- B Company, still in disgrace, was placed at Eora Creek, unable to engage.

- D Company, led by Bidstrup, advanced on the Oivi-Kokoda road and managed to ambush the Japanese, killing 45 before being outflanked and forced to withdraw—6 were killed, 3 went missing.

- C Company, under Dean, pushed forward on the main track but was ambushed at Hoi, with Dean killed crossing Faiwani Creek.

The attack was fragmented. Communications failed—the heavy 12kg radios, perfect for desert warfare, were useless in the jungle. Units became isolated, with no coordinated push.

A Company’s Brief Victory

Amid the confusion, A Company, led by Symington, took a side trail and stumbled upon Kokoda itself. Nearly unopposed, they entered the village on 8 August. Only a small Japanese security force remained, and they melted into the jungle.

The Australians had retaken Kokoda, but they were not safe.

They immediately began digging in, preparing for the inevitable Japanese counterattack. Each soldier had just 100 rounds of ammunition and two days’ worth of rations. They waited.

The Counterattack Begins

On 9 August, at dawn, 200 Japanese troops attacked through the dense rubber plantation. A Company repelled five separate assaults that day. At 5:00pm, another wave of 300 enemy troops advanced, getting dangerously close.

As night fell, the fighting intensified.

The Japanese began night raids, probing the perimeter, slipping through the darkness. Two Australian soldiers were found with their throats cut.

Dusk and Desperation

On 10 August, the pressure peaked. An allied aircraft flew over Kokoda, circling above with desperately needed supplies—but it wouldn’t land. Below, the Australians were running on fumes. No sleep. Low on ammo. Still, they held.

At dusk, the Japanese launched a concentrated final assault, chanting loudly as they attacked—a psychological tactic, equal parts intimidation and insult. "Australia, are you frightened?" they shouted.

The Australians answered with lead.

Bren guns fired until their barrels glowed, rounds hissing through the night air. Somehow, the attack was repulsed.

But it couldn’t last.

Retreat to Deniki

By 7:00pm, after two days of non-stop combat, the order was given: retreat to Deniki.

A platoon in the rubber plantation didn’t receive the withdrawal signal. Their sergeant, Jim Cowley, a 52-year-old WWI veteran, gathered his men and walked them out in total silence through the darkness, refusing to let panic overtake discipline.

The Australians abandoned Kokoda once again.

Japanese Reinforcements Arrive

On 12 August, the Japanese received reinforcements. Lieutenant-Colonel Tsukamoto’s 1/144th Battalion stormed Kokoda. Australian forces withdrew fully to Deniki.

The 2nd Battle of Kokoda had cost the 39th 15 lives, reducing their numbers to around 430 men. Japanese diaries later revealed the defenders had held off 1,200 Japanese troops, who spent six days trying to recover and regroup before pressing on.

Although the Australians lost Kokoda again, their resistance delayed the Japanese by three crucial days—shattering the myth of their invincibility. The enemy had carried only six days’ worth of rations, expecting a swift victory. Instead, they encountered stubborn, dug-in resistance.

Legacy of the Fight

The Australians’ stand at Kokoda may have confused the Japanese into thinking they faced a larger, more fortified force. Their caution bought time—for reinforcements, for supplies, for the next stand.

Ironically, the day after the withdrawal, an allied plane mistakenly dropped ammunition and supplies directly onto Kokoda—into Japanese hands.

But the tide was slowly turning.

On 2 November 1942, months after the chaos, the Australians would walk back into Kokoda—unopposed.

The jungle keeps its silence. But the story echoes still.

The Kokoda Track Campaign: Deniki to Alola

The Battle of Isurava (August 1942)

Withdrawal to Isurava | Honner Takes Command | The Battle That Defined Kokoda

A New Commander, A New Resolve

In mid-August 1942, under a darkening jungle canopy, the weary men of the 39th Battalion fell back once more—this time to a small clearing named Isurava. Pursued relentlessly by the Japanese and wracked by exhaustion, disease, and loss, they braced themselves for the next stand.

Lieutenant Colonel Ralph Honner, a barrister and athlete with a reputation forged in the battlefields of Libya and Crete, arrived to take command. He understood the gravity of the situation—and the raw courage of the men he now led.

He didn’t berate them. He didn’t question their toughness. Instead, he placed B Company—the most battered and maligned unit—in the position of honour: the left flank, the most likely point of Japanese attack.

And there, on the narrow ridge between Front Creek and Rear Creek, the Australians began to dig in.

Isurava: The Jungle Fortress

Honner knew Isurava offered no natural advantage—just steep jungle walls on one side and sheer drops on the other. But they made it work. In the middle of nowhere, they carved out a 400x400 metre perimeter, laid out killing fields, and prepped ambush zones.

Despite knowing they were outnumbered and outgunned, Honner ordered 24-hour patrols beyond the perimeter. These young Australians—some still teenagers—scouted Japanese positions and bought time. Many were cut off, ambushed, and barely made it back alive.

The enemy was massing. Honner could feel it. It wasn’t a question of if—but when.

AIF Arrives, Reinforcements (Sort Of)

On 16 August, Brigadier Arnold Potts departed Port Moresby with promises: the full 21st Brigade—including the battle-hardened 2/14th, 2/16th, and 2/27th Battalions—and a month’s worth of supplies.

But when he arrived at Myola, reality hit like a rifle butt. Only five days’ worth of supplies had arrived, and most pilots were civilians with no combat commitment. The 2/27th was held back in Moresby due to another campaign brewing at Milne Bay.

Potts had little to work with—just the tired 39th, the lightly trained 53rd, and two under-strength AIF battalions.

Still, they moved forward.

Isurava: Battle Lines Drawn

By 23 August, Potts was in command of the combined force. The 39th Battalion was whittled down to 150 men from an original 470. They hadn’t had a proper rest in over a month. But they held their ground.

On 26 August, the Japanese began their softening bombardments—mortars, Juki machine guns, and chilling jungle war cries. The night was alive with shadows. The jungle, a cauldron of noise and tension.

At dawn, the first wave hit.

Heroism in the Hills: Snowy Par & More

The battle began with moments of unbelievable courage.

Snowy Par, a lone sentry with the 39th, spotted a Japanese patrol just 3 yards away. He opened up with his Tommy gun and held them long enough to alert his unit. Smoke and chaos followed. Par rolled off a cliff to escape, then crawled back up to rejoin the fight.

The 39th fought tooth and nail all day.

That same afternoon, C Company 2/14th under Dickenson pushed into Isurava, hearing the thunder of battle as they approached. Captain Bidstrup of the 39th met them—bloodied, near spent—but still holding the line.

The next day, 27 August, brought even heavier attacks. Japanese troops, now estimated at 4,000, launched continuous assaults. The Australians—numbering just over 2,300, many in reserve—stood firm.

At 4:00pm, a full-frontal attack smashed into E Company’s line. The Aussies launched three counterattacks, engaging in vicious hand-to-hand combat. They threw the Japanese back.

This was no longer a militia force. They were hardened veterans now—Ragged Bloody Heroes.

The Tide Breaks: 28–29 August

On 28 August, the Japanese unleashed hell—mountain guns, shells exploding overhead, and massed infantry assaults.

Butch Bisset, of 10 Platoon B Company, led his men through 11 separate attacks, refusing to cede ground. Mortally wounded by a machine-gun burst, he died hours later in his brother Stan’s arms, just 150m past Con’s Rock.

The same day, Bruce Kingsbury led a bayonet charge with a Bren gun ripped from his fallen mate, Lindsay “Teddy” Bear. Kingsbury charged into the jungle, cutting down 30 Japanese soldiers before being killed by a sniper.

For that single, desperate act of bravery, he was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross—the first on Australian soil.

The Final Blow

On 29 August, the Japanese broke through the perimeter near the memorial site. C Company’s commander and four men were killed. Wounded flooded into the Isurava Rest House, where some soldiers were carried back down the track under fire.

Corporal Charlie McCallum, despite being wounded three times, held the line with a Bren in one hand and a Thompson in the other, emptying one while reloading the other. He helped his mates escape and calmly withdrew with both weapons. He was nominated for a VC but received the DCM.

Even in retreat, these men fought like lions.

Final Withdrawals

By 30 August, the 2/14th and 39th had been pushed to their absolute limits. At 5:00pm, Brigadier Potts ordered a withdrawal.

The numbers were staggering:

- 2/14th: 33 KIA, 6 missing, 28 wounded

- 39th: 76 KIA, hundreds more wounded or cut off

- The battalion was reduced to just 150 effectives

Cpl John Metson, shot in the ankle, refused a stretcher. He crawled for two weeks, eventually dying in the bush.

Private Fletcher and others stayed behind at the Isurava Rest House, hoping to regroup and get their wounded out.

The Battle of Isurava had cost dearly—but the Japanese paid in kind. Hundreds of their elite troops lay dead in the mud. Their advance was delayed over a week.

The Meaning of Isurava

Isurava wasn’t a victory in the traditional sense. But it was the moral and spiritual turning point of the Kokoda Campaign.

The myth of Japanese invincibility was shattered. The grit of the 39th was proven. And the legend of Kokoda was born.

Isurava’s granite pillars now bear four simple words: Courage. Endurance. Mateship. Sacrifice.

They were written in blood.

The Kokoda Track Campaign: Eora to Dump 1

(August -October 1942)

Final Action of the 39th | Tactical Withdrawals | Australia’s Largest Battle in the Owen Stanleys

Eora Creek: The 39th's Last Stand

After the brutal engagement at Isurava, what remained of the 39th Battalion fell back through the jungle to Eora Creek. On 31 August 1942, just 160 Australians answered roll call out of the 542 who had stood tall days earlier.

Their mates were gone—killed, wounded, or cut off in the retreat. But the fight wasn’t over.

At Eora Creek, the Australians dug in, determined to delay the advancing Japanese and protect the withdrawing Allied forces. The ground shook with artillery fire as the Japanese rained shells on the wounded and weary. Even soldiers in the field hospital picked up rifles and limped back to the front.

This was the 39th’s last official stand on the Kokoda Track—and they gave it everything.

Tactical Brilliance in the Jungle

Outnumbered, underfed, and outgunned, the Australians pulled off a tactical masterpiece.

Company by company, platoon by platoon, they executed a series of leapfrogging withdrawals—holding the line until their mates passed through, then breaking contact with the enemy just 20–30 metres away. They repeated this process again and again, falling back slowly but in control.

It wasn’t just survival. It was strategy.

Weapon pits from these delaying actions are still visible today beside the track. Ghosts of resistance carved into the mud.

The 39th handed the baton to the fresh units of the AIF, and then they faded into history. But not before proving their worth.

Templeton’s Crossing & Dump #1

The retreat passed through Templeton’s Crossing #2, named in honour of Captain Sam Templeton, the first commanding officer of B Company, 39th Battalion. His name carried weight among the diggers.

Then came Crossing #1, also known as Dump No. 1—a notorious section of the track where exhaustion, terrain, and enemy contact converged in one of the campaign’s hardest passages.

From 31 August to 5 September, fighting continued as the Australians delayed the Japanese advance. Losses mounted:

- Australia: 21 KIA, 54 wounded

- Japan: 43 KIA, 58 wounded

The jungle didn’t show favour. Only grit decided who lived and who fell.

Australia Pushes Back: The Return to Eora Creek

Fast forward to late October. The momentum had shifted. Australia was no longer just holding—they were advancing.

From 22 to 29 October, Eora Creek became the site of Australia’s largest battle in the Owen Stanley Range.

The 6th Brigade—toughened in the jungle and hungry to reclaim ground—took on a deeply entrenched Japanese force. The enemy had fortified the area with five artillery guns, machine gun emplacements, and mortars, all dug into elevated positions guarding the creek.

They had also constructed a central keep, protected by four or five radiating gun posts and Japanese spotters embedded throughout the high jungle. This was a fortress.

And it was the only water source on the ridge.

The Assault Begins

The main Australian assault on 22 October was met with brutal resistance. Soldiers scrambled up steep terrain under withering machine gun fire and hand grenades. Many died trying to cross the creek—logs and shallow fords offering little cover.

But the Australians were relentless.

On 26 October, a new tactic was employed: a wide flanking manoeuvre through thick jungle. The 2/3rd Battalion, after trekking for days in silence, attacked from the high ground northwest of Eora Creek.

They caught the Japanese off guard.

After five days of fighting, the Australians finally broke the defensive stronghold. Around 69 Japanese troops were killed, and many more wounded or scattered. Some were seen fleeing down jungle slopes as the Australians surged forward.

Corporal Lester G. Pett was credited with taking out four machine gun posts by himself.

The Cost of Victory

It was a hard-fought win, but it came at a price:

- Australian casualties: 412 killed or wounded

- Japanese casualties: 244 total

It was here that advancing troops made a chilling discovery—evidence of Japanese cannibalism, including a parcel of human flesh. The toll of war in the jungle went beyond the physical. It broke boundaries of horror.

But through it all, the Australians pressed on. They weren’t just fighting for ground anymore—they were fighting for memory, for mates lost, for every inch they’d been forced to give up.

The Kokoda Track Campaign:

Templetons Crossing to Kagi (September 1942)

Through The Gap | Myola’s Lifeline | Arrival at Kagi

The Gap That Wasn’t

In the high ridges of the Owen Stanley Range lies what was once thought to be a narrow choke point—The Gap. Australian command believed it could be held by a single soldier and a machine gun.

They were wrong.

The Gap, it turned out, spanned nearly 7 kilometres, wide enough for aircraft to fly through. It wasn’t a fortress. It was a corridor.

But it was also the pathway to survival—and the next step on a long retreat.

The Forgotten Bomber

Near the Gap, in a remote fold of jungle, lay the shattered remains of a B-25 Mitchell bomber named The Happy Legend. Disappeared on a bombing run in December 1942, it wasn’t discovered until February 1943. The wreckage was strewn across the jungle, untouched until 2002, when live ordnance made recovery possible.

Even then, the remains of two airmen couldn’t be recovered until 2006. The bombs had to be defused first.

Today, their story is silent. But the jungle remembers.

Myola: The Lifeline of the Track

Discovered by Lt Herbert Kienzle, a veteran planter turned soldier, Myola 1 and 2 were two dry lake beds hidden in the grasslands. Turned into vital re-supply zones, they became the beating heart of the track’s survival.

From early August, C-47s and DC-3 “biscuit bombers” made daring flights over the Owen Stanleys, dropping tonnes of food, ammunition, and medical supplies to troops retreating—and later advancing—along the Kokoda Track. In the thick of things, they delivered up to 5 tonnes per day.

But only half the drops hit their mark.

Some missed by kilometres. Others vanished into the jungle.

The Rearguard Holds

By 2 September, Japanese troops were moving around Templeton’s Crossing, probing the rear defences. A standing patrol spotted them—and killed ten. But the enemy was closing in fast.

Lt Colonel Caro, commanding the 2/16th Battalion, saw the writing on the wall. The Australians had to move—soon—or be outflanked and surrounded.

Retreat and Recovery at Myola

On 4 and 5 September, the battered 2/14th and 2/16th Battalions arrived at Myola.

There, for the first time in weeks, they received a hot meal. Clean clothes. Fresh socks. Some men’s boots had rotted away entirely.

But Myola wasn’t safe. Stores were being dismantled and destroyed, or buried in haste. The Australians were falling back, and the Japanese were advancing.

On 5 September, the rearguard held firm. But four Australians were killed as the Japanese pushed closer.

Buried Firepower

In the rush to fall back, a massive cache of explosives was hidden at Weapon Pit, Myola 1—including 2-inch and 3-inch mortar rounds, No. 36 hand grenades, and boxes of boots with WWII steel-plate heels.

A protective cage was installed in 2012 to preserve the site and protect those who pass by.

Nearby, the wreck of a P-40 Kittyhawk fighter—shot down on 22 November 1942—marked the jungle with twisted metal. The pilot bailed out and walked to Kokoda. But many others were not so lucky.

Kagi: A Moment to Breathe

By 5 September, the Australians reached Kagi—a supply drop zone and lookout post perched high in the Owen Stanleys. No fighting happened here. But it was more than just a checkpoint.

Kagi was where the 39th and 2/27th Battalions regrouped, rested, and prepared to fall back further to Efogi and Mission Ridge.

It was also the home of Havala, one of the most well-known Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels. His hands once carried wounded diggers over mountains, through rivers, and back to safety. His smile still lingers in stories told along the track.

Here, under a wide sky and thick canopy, the diggers had a moment to catch their breath. But they knew what came next.

The real mountain still lay ahead.

The Kokoda Track Campaign:

Kagi to Menari (September 1942)

Brigade Hill | Mission Ridge | The Battle of Butcher’s Hill

The Calm Before the Storm

After the long retreat through the Owen Stanleys, Kagi felt like a momentary pause. Nestled near a Seventh Day Adventist mission hut, it gave the weary 39th Battalion a brief spell to regroup—if only in body, not spirit.

It was here that the 39th Militia, down to just 180 men (half of whom were unfit to fight), finally handed over their battered gear to the arriving 2/27th Battalion. The automatic weapons, grenades, spare rations, and blankets passed hands with a solemn understanding: their time on the front was over—for now.

But the war was far from finished.

The Rise to Butcher’s Hill

The route from Kagi to Mission Ridge—or Butcher’s Hill, as it would come to be known—was the original wartime track. The newer trails, Efogi 1 and 2, came later. But this ground, thick with mist and memory, was the stage for one of the Kokoda campaign’s fiercest battles.

By 5–7 September, the 21st Brigade, comprising the 2/27th, 2/14th, and 2/16th Battalions, had consolidated here. Nearly 1,500 Australians prepared to meet the Japanese head-on.

Mission Ridge saw the 2/27th Battalion (588 fresh troops) dig in along the forward slope. The 2/14th and 2/16th (about 400 troops, only 35% of original strength) stayed further back on Brigade Hill as a mobile reserve. Behind them, at Brigade HQ—affectionately dubbed "Ruthless and Toothless"—100 seasoned veterans stood ready. Among them, Captain Langridge and two platoons from D Company 2/16th.

The Lantern Parade

On the night of 7 September, Australian soldiers watched in eerie silence as Japanese troops descended the ridgeline toward them in what would later be known as the Lantern Parade. It was surreal—lanterns bobbing in the dark, illuminating the approaching enemy.

The Aussies didn’t have the heavy machine guns to reach them. But Brigadier Potts called in an airstrike for dawn.

The morning sky roared with the engines of 8 Marauders and 4 Kittyhawks, strafing and bombing Japanese lines. It was the first time the enemy had experienced aerial bombardment. It boosted Aussie morale and stunned the Japanese.

But this would only be the prelude.

The Battle of Brigade Hill (8 September)

At 4:30am, Major General Horii launched a three-pronged attack against the Australian position—classic Japanese tactics: frontal assault, flank envelopment, and rear disruption.

The Australians held.

For hours, the 2/27th’s forward position on Mission Ridge repelled wave after wave. By nightfall, many hadn’t even had a chance to remove their jumpers. They were out of water. Exhausted. And dangerously low on ammunition.

In total, they’d used:

- 1,200 grenades

- 6,000 bullets

- 6 Bren guns

And they’d lost 37 men in the process.

Cut Off in the Jungle

Overnight, three Japanese companies—roughly 400 men—scaled the western cliffs behind the Australians. The cliffs were thought impassable. That was the assumption.

That was the mistake.

The Japanese climbed like ghosts, slipping behind the lines undetected. By dawn, they had set up sniper nests and machine guns in the trees, right between Battalion HQ and the 2/16th Battalion.

Brigade HQ—along with all reserves of food, water, and ammunition—was now cut off. The only track leading to Menari, the escape route, was in enemy hands.

The Valley of Death

At dawn, Potts and his aide, Lance Corporal Gill, left their HQ for a moment of privacy. Gill was shot dead by a sniper.

Potts realized the full scope of the ambush. The track had fallen silent, but soon it erupted with gunfire. Brigade HQ was under attack—from less than 30 metres away.

This wasn’t just a battle. It was an encirclement.

The Man of Kokoda: Nishimura

On the same day, 2/14th and 2/16th launched a counterattack to retake the knoll between Brigade HQ and the front line. At the heart of the Japanese defence was Kokichi Nishimura, commander of a 42-man platoon.

In fierce hand-to-hand combat, his platoon was wiped out. Nishimura himself was wounded twice but survived, hiding beneath tree roots until he could slip away. His account of this desperate battle—later titled The Saddle—describes the carnage of that day.

The Japanese had chosen to hold, not advance. To bait the Australians into slaughter.

A Desperate Breakthrough

Brigadier Potts ordered a direct assault to clear a path back to Brigade HQ. Four companies of 2/16th and elements of 2/14th were tasked with the impossible.

They were told to fix bayonets.

At 2:59pm, in the pouring rain, the Australians rose from the jungle and charged the position. The 2/14th, advancing up the right flank, were stopped just 20 metres in by a wall of machine gun fire.

Men fell.

Captain Nye and Charlie Mac, a hero from Isurava, were both killed. From the 2/16th, only ten made it through the first wave.

Still, Potts ordered another charge. This time led by Captain Langridge, Bluey, and 50 more men. They too were gunned down.

In the mud and blood, Potts prepared to order a third attack—essentially a suicide mission. But reason prevailed. The order was rescinded.

The Angels Never Left Them

Through it all, the Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels moved silently, tirelessly, fearlessly—carrying the wounded under fire, dodging bullets and mortars, hauling stretchers across slippery jungle.

They weren’t soldiers.

They were saviours.

Aftermath: The Fall to Menari

By dusk on 8 September, Potts ordered a withdrawal to Menari. Brigade HQ took the main Kokoda Track—the only viable exit. Meanwhile, the 2/14th and 2/16th Battalions moved under cover of darkness along a narrow jungle track, carrying their wounded through thick bush. They reached Menari the following day.

At the rear, Captain Lee’s B Company (2/27th) held firm. Instead of merely defending, Lee, Captain Skipper, and five men launched a surprise counterattack. Their automatic weapons blazed through the night, buying precious time for 46 wounded and 20 stretcher cases to escape.

Others weren’t so lucky. An entire detachment from the 2/27th lost their way and were trapped behind Japanese lines. Some would not be rescued for 2 to 4 weeks. Maggots were used to treat their wounds. Rations were reduced to a single can of bully beef per day.

On 4 October, the 3rd Battalion finally reached Brigade Hill. They found the bodies of their comrades—some still on stretchers, others slumped in trenches, rifles still in hand.

The cost:

- Mission Ridge: 39 Australians KIA

- Brigade Hill: 62 Australians KIA

- Japanese casualties: Estimated in the hundreds

Brigadier Potts had delayed the enemy by three days—at staggering cost.

Damien Parer’s Lens

Among the chaos walked Damien Parer, camera in hand. He filmed the retreat, captured the grit and heartbreak, and later earned an Academy Award for Kokoda Front Line.

Parer would die two years later filming US Marines on Peleliu, but his images of Kokoda remain immortal.

The Kokoda Track Campaign:

Menari to Nauro (September 1942)

Retreat, Starvation, and the Strain of Pursuit

The Road to Nauro

At Menari, on 6 September, the shattered 39th Battalion stood for what would become an iconic photo—Lt Col Ralph Honner addressing his Ragged Bloody Heroes. The men, starving, shoeless, and racked by disease, lined up for a final parade before turning their faces toward Koitaiki.

They were emaciated. Some had scrub typhus, others dysentery. Many had no boots. They’d cut the seats out of their pants to ease the agony of jungle sores. And still—they marched.

By 9 September, 2/14th and 2/16th reached Menari just ahead of a Japanese push.

The retreat pressed on.

Brigadier Potts, commanding just 300 men, had no position capable of halting the Japanese between Menari and Ioribaiwa. With no choice, he ordered a withdrawal.

The battered 2/14th and 2/16th were merged into one unit. Late that afternoon, they pushed beyond Nauro Village and up the Maguli Range.

Lost & Starving: The 2/27th

Eventually, the 2/27th Lost Battalion reached Menari—only to find it already behind Japanese lines. Their journey had been slow, their men grievously wounded.

Of the 46 seriously wounded, 20 required stretchers. Some with lost limbs walked anyway.

Without food for over two weeks, they evaded patrols, skirted ridgelines, and crawled their way south to safety.

The Enemy's Strain

Japanese supply lines were stretched thin. Evidence of cannibalism was discovered—parcels of human flesh, bones stripped of meat, a body decapitated, another dismembered.

This wasn’t desperation. It was starvation.

Still, they pursued.

Brown River & Efogi 2

North of Nauro, the Brown River flats gave the Allies a slight advantage. Supplies were dropped with some success.

But the enemy kept pressing.

Meanwhile, Efogi 2 became a site of remembrance.

Kokichi Nishimura, survivor of the Battle of Brigade Hill, returned decades later to find the remains of his fallen comrades. He built a memorial at Efogi 2—stone by stone, alone, with the help of local children.

He fetched the stones by hand, even organized planes to bring them in. On 5 July 1989, he placed the final inscribed rock: "To The Loyal War Dead.”

He lived in Efogi for 20 years, his tribute standing not just as a monument, but as a message—from one soldier to all.

The Kokoda Track Campaign:

Nauro to Ua-Ule Creek (September 1942)

Ioribaiwa Ridge | Japanese High Tide | The Turning Point of the Campaign

The Japanese Push to Ioribaiwa

By 11 September 1942, the Japanese advance had reached its furthest point: Ioribaiwa Ridge. It was the second staging post on the Kokoda Track for Australian forces—and it would be the furthest the Japanese would ever get toward Port Moresby.

The 21st Brigade, once numbering 1,750 soldiers, was now down to just 305 men. Reinforced by the 3rd Militia Battalion (400 men) and supported on the flanks by 2/6th Independent Company and composite units of 2/14th and 2/16th, they dug in and prepared for what was coming.

It came fast.

The Fight for the Ridge

On 13 September, three battalions from the AIF’s 25th Brigade arrived—2/25th, 2/31st, and 2/33rd—bringing 1,800 fresh troops into the battle. General Ken Eather immediately devised a twin flanking manoeuvre. But the jungle’s chaos is no friend to strategy.

The 2/31st Battalion faltered. Lost contact. Fell into confusion.

Meanwhile, the 3rd Battalion on the right was ambushed by a Japanese patrol. The Japanese secured the high ground between the 3rd and 2/31st—while the Australians slept, rifles out of reach.

Stubborn Defence, Brutal Conditions

Australian firepower was bolstered with Vickers medium machine guns and three-inch mortars, but still no artillery.

The Japanese, on the other hand, had eight artillery guns pounding the ridge.

Even worse: wounded men weren’t evacuated. The Japanese were holding the rear. Instead, injured troops were retained at the front, closer to enemy lines than their own medics.

Despite being outgunned, the composite 2/14th and 2/16th units held firm. On 16 September, they regained their independent identities.

Australian casualties: 49 KIA, 121 wounded. Japanese: 40 KIA, 120 wounded (of 1,650 troops).

The Commando Ambush

Back on 15 September, a 23-man patrol from C Platoon Commando crawled for 8 hours through jungle from Ofi Creek to flank a Japanese Type 94 mountain gun.

They waited two hours in silence before launching a deadly grenade assault—destroying the gun and its crew. It was a bold and clinical strike against the very artillery that had been pounding Ioribaiwa Ridge for days.

Ua-Ule Creek: Tea, Biscuits, and Strategy

Farther down the track, Ua-Ule Creek became a minor yet important site.

A Salvation Army welfare tent was pitched here—serving hot tea and biscuits to soldiers slogging back from the ridge. But this quiet reprieve was paired with serious decisions.

General Ken Eather saw the writing on the wall. The 21st Brigade was exhausted. Supplies thin. Communication lines long. He ordered a withdrawal to Imita Ridge—a more defensible line just 7 km away.

But not without resistance.

General Allen, back in Port Moresby, agreed with one firm condition:

“There won’t be any withdrawal from Imita, Ken. You’ll die there if necessary.”

Final Clash Before Withdrawal

On 17 September, Aussie forces began retreating over the Ua-Ule Creek Valley. That same day, a brilliant ambush was staged in the kunai grass near present-day Ioribaiwa Village.

A 4-man Aussie patrol lured a group of 50 Japanese into a deadly trap. Waiting in silence, C Company 2/33rd Battalion (80 men) opened fire with hand grenades and mortars, killing the entire force in under 2 minutes—a thunderous, precise counter-strike.

Japanese records claim only

2 were killed, but survivors speak louder than paper.

The tide was turning. Ioribaiwa was as far as the Japanese would get. Port Moresby lay just over the hills—but it would never fall.

The Australians, bloodied but not broken, were about to reclaim the track.

Final Battle Overview: Eora Creek and Retaking Kokoda

By 22 October 1942, the Australians had turned the tide.

General Horii’s forces, already battered by Templeton’s Crossing and the push through the Owen Stanleys, were now losing ground. His final line of defence—high above Eora Creek—was not fully prepared.

The Australians launched a frontal assault across a narrow stream with no bridges, under machine gun and mortar fire. After five days of heavy losses, they shifted tactics.

On 26 October, the 2/3rd Battalion moved through the jungle, circling to the northwest of the Japanese position. After two days of hard trekking, they launched a surprise attack, overwhelming the defenders.

Eora Creek became a valley of death. The water ran red with blood. The air stank of cordite and decay. But the Australians had broken through.

Reclaiming Kokoda

The Japanese retreat was in full motion. On 2 November 1942, members of the 2/31st Battalion entered Kokoda village unopposed. The Japanese had withdrawn two days earlier.

By mid-afternoon, the Australians were fully established. The Kokoda Plateau and airstrip were back in Allied hands.

On 3 November, Major General Vasey arrived by air. Two ceremonies marked the moment—one at the plateau, another at the airstrip. Papuan carriers were honoured alongside the soldiers they had carried and cared for.

The return of Kokoda held deep symbolic weight. The village’s name had become etched in the national consciousness. Now, after months of brutal jungle warfare, the first great chapter of the Kokoda campaign had ended.

But the war raged on.

The Road Beyond Kokoda

The Australian advance did not end at Kokoda. Fierce fighting continued at:

- Oivi to Gorari (121 KIA)

- Gona (380 KIA)

- Buna (312 KIA)

- Sanananda Track (430 KIA)

- Sanananda Village (220 KIA)

The final battles stretched into January 1943, as Australian and American forces drove the Japanese back toward the beaches where they had landed.

The Kokoda Track Campaign had ended. But the cost—and the legacy—would echo through generations.

Ready to work with The Kokoda Track Company?

Let's connect! We’re here to help.

Send us a message and we’ll be in touch.

Or give us a call today at (03) 9123 6409

Agency Contact Form

More Marketing Tips, Tricks & Tools